As a 9-Ball pool player I always take a detour to think about the right colors and numbers, e.g. yellow/white = 9…

That was the real give-away for 50% of Ravvie’s 2% …

I missed both of the base 13 examples, but yes they look correct.

My first attempt following the hint from Mrs R was 7 + 9 + 11 in base 9. Then I realised that the digit 9 doesn’t exist in base 9, so that was a bit of a fail.

I think the ‘base’ answer requires two striped balls and one solid ball.

I didn’t know that. Once I’d figured out that it couldn’t work with the numbers as they were, I started to think “outside the box”, i.e. I knew there had to be something else. 6 and 9 being reverse is quite well known, so I’m suprised at the 2% figure.

Maybe 98% of people don’t think outside the box?

As a group we have done pretty well with this puzzle, finding three very different types of solution.

I’ve been helping my 13 year old grandson (2nd year in Senior School) to consolidate his maths. They are coming to the end of Key Stage 3 Higher level.

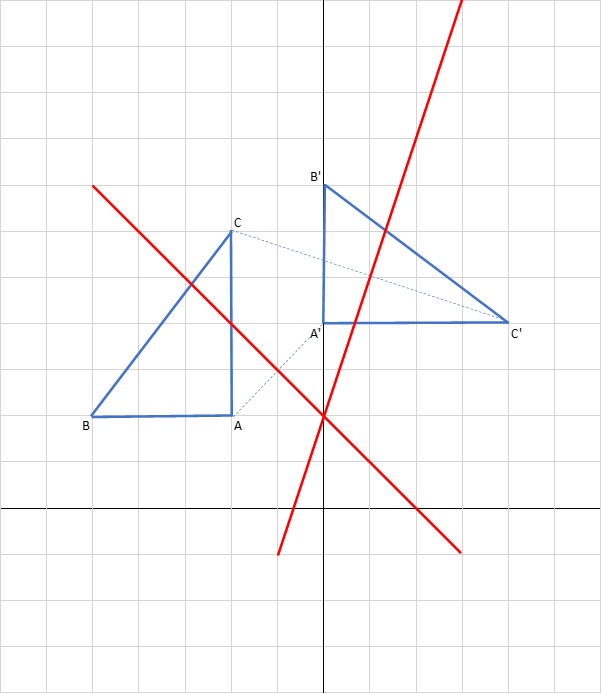

This week they are covering Transformations ie Translations, Reflections, Rotations and Enlargements.

Concerning Rotations, I can show him how to generate a rotation by using tracing paper to copy the shape, put the pencil firmly on the co-ordinates of the point of rotation, turn the tracing paper (say) 90 deg clockwise, then mark out the rotated shape beneath the tracing paper. The diagram below has a couple of examples.

However, when he is given two positions of a given shape, and has to identify the co-ordinates of the point of rotation, I can only do that by Trial & Error. I trace one of the shapes, then use my pencil to pin the tracing paper whilst turning it to see if it will lay over the other shape. But it does take quite a bit of fiddling around !!

Anybody got a more predictable method ? either graphical or mathematical ?

This is a brain teaser for me, so any help will be most appreciated !!

Cheers

Don

The distance of each point from the centre of rotation remains unchanged. In your example, using (0,2) the top corner starts 2 back and 4 up from the centre of rotation and ends 2 up and 4 along.

The centre of rotation must therefore lie on the perpendicular bisector of the line joining the corresponding points. This is the line that is equidistant from the corresponding points.

So a practical method is to draw the perpendicular bisector using a compass centred on the corresponding points. Then repeat with a second pair of points. The centre of rotation is where these bisectors intersect.

The method works for all shapes and angles of rotation.

I would try and draw it but my son went back to university (Maths at Leeds) yesterday and has taken the graph paper and compass!

Thanks Ravvie.

We were planning perpendicular bisectors next. I’ll show him some simple “trial & error” examples of rotations first, then let him know that we’ll come back next week to a more reliable process of finding the centre of rotation.

Fibonacci’s Three Birds Teaser

This teaser is so old that originally it was written in Latin. Excerpt from from Fibonacci’s “Liber Abaci”, 1202:

Quidam emit aves 30 pro denariis 30. In quibus fuerunt perdices, columbe, et passeres: perdices vero emit denariis 3, columba denariis 2, et passeres 2 pro denario 1, scilicet passer 1 pro denariis ½. Queritur quot aves emit de unoquoque genere.

Fortunately it has been translated into English as follows:

A man buys 30 birds of three kinds (partridges, doves, and sparrows) for 30 pence. A partridge costs 3 pence, a dove costs 2 pence, and 2 sparrows cost 1 penny, that is, 1 sparrow for ½ penny. How many birds of each kind does he buy?

22S, 5D, 3P seems to fit the bill.

Don your grandson is lucky to have a grandfather who’s not only willing but equipped to help.

Yes, it does fit the bill.

Would you like to show your method? As with several other teasers we’ve had, there are various approaches.

The method that Fibonacci used was rather neater than my effort!

The technique that I used is called “intelligent trial & error”

That’s a term that I’ve just coined !!

It’s not quite “Iteration” and it’s not simply wild guesses.

- He could only buy 10 P’s or 15 D’s or 60 S’s if he only bought one breed. By inspection, this suggests I limit my trials to the high teens or low twenties for the Sparrows. And a low headcount for the P’s and D’s.

- No matter how many Doves he buys, they will always cost an even sum of money, 2p, 4p etc

- Odd P’s 1, 3 etc, will cost odd pence and need to be balanced by pairs of Sparrows costing odd pence eg 18 Sparrows, 22 Sparrows etc

- Even P’s 2, 4 etc will cost even pence and need to be balanced by pairs of Sparrows costing even pence eg 20 Sparrows, 24 Sparrows etc

On the above basis, the number of “trials” needed to get 3, 5 and 22 was pretty small.

I like the phrase!

My approach was broadly similar, perhaps more “trial” than “intelligence”. I tried a couple of options and looked for patterns, for example swapping a dove for sparrows changes the bird count by three. It helped that I envisaged that I was in a sweet shop optimising my 30 pence pocket money on three types of sweet (though in reality it used to be 6d). I used to be good at that!

Fibonacci solved it by considering buying bundles of two bird types where the average cost is one penny. There are just two:

Bundle A: 1P + 4S = 5 pence

Bundle B: 1D + 2S = 3 pence

By inspection, the only way to total 30 pence is 3x5 + 5x3, namely 3A + 5B. This gives 3P + 5D + 22S. The solution is unique assuming that “birds of three kinds” means at least one of each.

Here’s another one from the New Scientist people might like to try. Being a psychologist and not a mathematician, this is slightly beyond me, but I’m guessing Pythagoras’ Theorem and Pi play a role) but I might be completely wrong.

First run through in my head suggests 180cm.

But I really need to sit down with pen and paper and check this one carefully.

Still haven’t got the pen and paper out to check, but …

I basically used Sin 30 = 1/2

And of course Sin = Side Opposite/Hypotenuse

I also worked with the Radius of the small barrel as 1 decimeter

Which seemed to make the numbers more manageable

Hopefully, tomorrow I will put pen to paper.

Don,

That’s the way I did it, so I agree with your answer.

There is also a visual solution using equilateral triangles. Arguably it avoids maths knowledge such as Pythagoras or trigonometry etc. I can draw it in my head, I will see if I can draw it for real.

That was a really neat teaser. Thank you !

I’ll try to find time over the weekend to illustrate my solution. As the saying goes … a picture is worth a thousand words